Reading Psalms: 1. Hebrew Poetry Repeats Itself

What is poetry?

On one hand, to ask this kind of question seems a bit pointless: poetry is ... well ... poetry, isn't it?! We know it when we see it.

Yet, on the other hand, poetry is quite difficult to define. We can describe characteristics of poetry with relative ease: meter and metaphor, simile and imagery: it engages senses; it invokes imagination; it stirs emotion. Nevertheless, it doesn't take much reflection to realise that these elements of poetic technique are not essential for all - or even much - poetry; we can also be 'poetic' without writing poetry (see the previous sentence!).

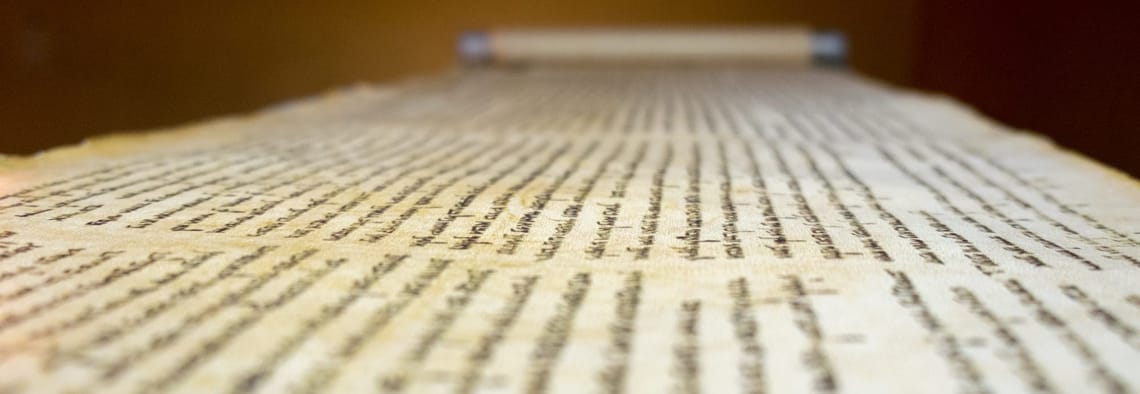

When we add the realities that the Old Testament's poetry is both ancient and in Hebrew, the problems are compounded. If you’ve been attentive to your different Bible translations over the years you may have noticed that some passages are formatted as poetry in one translation and as prose in another, as the translators struggle to figure out if they are reading prose or poetry: it's not even the case that 'we know it when we see it'.

There are, however, some characteristics to Hebrew poetry that, are identifiable and worth knowing about, although only the first makes its presence felt in English. We'll look at the second and third in the next article.

The first technique is called parallelism.

'Parallelism' is not a perfect description since parallel lines, while next to each other and paired together, never actually connect. The sense of Hebrew parallelism is more about the pairing across two (or more) lines, and they are designed to be read in light of each other.

If there had to be a basic summary of what biblical parallelism is, it’s that ‘Hebrew poetry repeats itself’.

Psalm 2 gives us as a classic example. Notice how every idea in Psalm 2 occurs in pairs. In verse 1:

Why do the nations rage

and the peoples plot in vain?

Or, in verse 3,

Let us burst their bonds apart

and cast away their cords from us.

Each pair is in parallel: synonymous repetition. And once we see its existence, it’s impossible to miss!

The goal of reading parallel lines isn’t so much a forensic analysis of each single word and phrase in isolation (‘the author speaks of “bonds” in v3a to signify … but in v3b he deliberately choses “cords” so as to …’). The goal is to read the parallel lines together (‘the nations see God as oppressive to their freedom and they desire to break free of his “restraints”’).

Parallelism doesn’t just occur in pairs, either. Sometimes we encounter triplets and quadruplets. For example, Psalm 1 opens with a triplet; it says the same thing in three different ways:

Blessed is the man who:

walks not in the counsel of the wicked,

nor stands in the way of sinners,

nor sits in the seat of scoffers;

As we see this technique, which is everywhere in Hebrew poetry, how can our awareness of it help us hear God better? For now, we can focus on three things:

First, it can sometimes be easy to lose the forest for the trees when we read Old Testament poetry. The forest (the big picture of what God is saying in the poem) can be swallowed up for all the trees (all this repetition). A useful way to regain the sense of a passage is to temporarily remove the repetition and build a picture of the overall meaning. I often like to write out the summary point of each couplet / triplet / quadruplet to find that overarching meaning. This is perhaps the most useful thing to hold onto if all this repetition is new to us.

Second, as useful as that simplification is, we need to remember that the repetition is there for a reason. The repetition of ideas builds a picture which then evokes images, ideas, and our affections. It’s not enough for us to simply identify the idea behind the repetition (e.g., Psalm 2:1: the nations are in rebellion against God). To leave it there is to reduce the poem to propositions, when poetry is about so much more. We must embrace the imagery (raging, plots, conspiracies, defiance … in contrast to God’s derision in response). The evocation and affections conjured by the imagery is as much part of God’s communication to us as the proposition lying at its core and which controls the imagery.

Third, when we encounter changes in the repetition, ideas are highlighted as significant. When the parallels go from couplets to triplets (or vice versa), the poet could be highlighting an idea, or concluding a stanza. When the parallel is not synonymous (saying the same thing differently), our attention is drawn to contrasting or ‘building’ parallels.

Take, for example, Psalm 2:2b:

Against the LORD

and against his Anointed (Messiah/Christ)

The parallel is there, but it’s a ‘building’ parallel, and, having thrown God and his Christ together in this pair, the next verses of the Psalm twin the two figures: to rebel against one is to rebel against the other. The two figures are distinguishable, but inseparable. How we treat the Son / Christ / King is the same question of how we treat God.

Or, in a different signification, the Psalm concludes with no parallel at all: ‘Blessed are all who take refuge in him’. Its variation highlights its importance for us to embrace the Son, and leaves us with a stark action to enact from the Psalm.

Subscribe to my newsletter to get the latest updates and news