Reading Psalms: 2. Poets of Rare Words

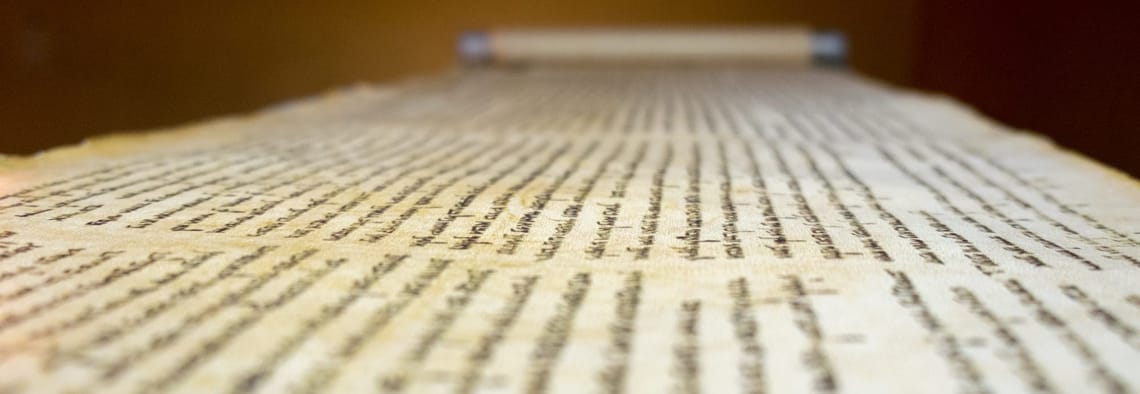

In the last article we saw that the first and most distinct feature of Hebrew poetry is its repetition: lines of poetry in parallel to create integrated imagery.

In this article we cover two further characteristics. They are much less obvious to the English reader because the process of translation tends to remove it. The translators aren't being unfaithful as they do this; it's part-and-parcel of translation.

So why should we bother about them, then? The main reason is so we can maintain confidence in the translations we have before us, because they make their presence felt in such a way that they can undermine that confidence if we aren't aware of what is happening.

The two characteristics make their presence felt when we read the footnotes in our Old Testament poems, or read a new Bible translation (especially the NIV11) from our familiar ‘old faithfuls’. Together, these two features can be summarised as 'Old Testament poets were men of rare words'.

It may sound strange to our ears, but Hebrew poetry leaves verbs behind and they become rarer. It still has them, but it has them far less frequently than it does in prose. In fact, there was a period of time in Hebrew translation where, at a loss to know if parts of Jeremiah were poetry or not, some scholars resorted to a statistical analysis of verbs in ratio to nouns to make their decision!

While this is not something the average reader needs to worry about, there is one consequence for us that we will meet from time to time. Translators quite often have to make a decision about the tense of the verb with very little contextual help, and fewer verbs to work with (and sometimes no verb at all!). Sometimes, a verse may well be legitimately translated in several different ways. For example, in the most extreme of examples, the following could all work:

‘The Lord saves you’

‘May the Lord save you’

‘The Lord has saved you’

Sometimes a translation will give a heads-up to this problem in the footnotes (but never all the time). Mostly, however, we see the problem emerge when we move our reading from one translation to another, and no more so than in NIV11.

Take Psalm 18:3. The ESV and NIV84 say:

‘I call to the Lord … and I am saved from my enemies’

But the new NIV (2011) says:

‘I called to the Lord … and I was saved from my enemies’

So, which is correct? Both? Neither? Yes. And no.

It sounds impossible to our ears, but 'tense' is much less important in many ancient languages than in modern ones. These ancient languages are much more interested in situation, relationship, or perspective.

Let me try to put it in a practical way. Take Psalm 18 again. Wouldn't both tenses be true? Presumably, when David prayed Psalm 18:3 it was very much a present tense! And he was probably very tense as he prayed it (haha)!!! But afterwards, after the event and when he wrote it, it was a past tense.

The final distinguishing feature of Hebrew poetry is that it has a really high instance of rare and unusual words. Or, better: rare and unusual to we who live thousands of years later. Hebrew prose has a very simple set of words, but Hebrew poetry has a whole set not normally used, especially because it’s trying to find all those synonyms to fit with its habit of repetition.

The consequence of this is that a lot of these Hebrew words only occur once or twice in the Bible, and only in poetic (metaphoric) contexts. Determining what they mean can at times be tricky! So, depending on the Bible you have, you’ll notice that the Psalms have that ever-present footnote: ‘The meaning of the Hebrew is uncertain.’

If they are so rare, how do we know what the words mean? Is it just guess work? Thankfully, for the most part, no. We are able to rely on Greek translations from the 2nd century BC to know what they might mean, and other ancient languages similar to Hebrew often have similar words in their languages. And, we have all those parallel lines to help us, too!

When we see those footnotes, or pick up a new(er) translation of the Psalms compared to what we’re used to, it can be quite unsettling. Once we are aware of what is going on behind the scenes, however, we regain confidence. They are still the same psalms, even if they are translated a little differently in tense and vocabulary!

And maybe the jolt can jar us enough to see afresh what God is saying in these poems. And that’s something truly to be thankful for.

Subscribe to my newsletter to get the latest updates and news